Bon Voyage: Professor and Students Set Sail to World's Largest Single Volcano

Research Cruise to Study Formation of the Underwater Volcano Tamu Massif

On October 5, William Sager, professor of geophysics in the College of Natural Sciences and Mathematics, departed on a research cruise with the goal of understanding how the world’s largest single volcano, Tamu Massif, was formed.

On board with Sager are seven University of Houston students from the Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences – six graduate students, one undergraduate – enrolled in a course called “Special Topics in Practical Marine Geophysics at Sea.”

Students Will Gain Hands-On Experience

Video: Return to Tamu Massif During the 36-day cruise, Sager and his students will collect data that will help them understand how Tamu Massif was formed. Along the way, the students will gain valuable hands-on experience that will prepare them for careers as geophysicists.

Video: Return to Tamu Massif During the 36-day cruise, Sager and his students will collect data that will help them understand how Tamu Massif was formed. Along the way, the students will gain valuable hands-on experience that will prepare them for careers as geophysicists.

“The students are going to learn a tremendous amount by being there and working on data,” Sager said. “They will learn by doing.”

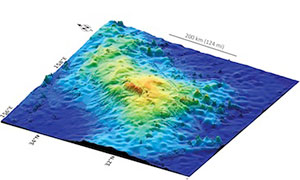

At 120,000 square miles – roughly the size of New Mexico – Tamu Massif is the largest known single volcano on Earth, located in the Pacific Ocean about 1,000 miles to the east of Japan. In 2013, Sager, who has been studying Tamu Massif for over 20 years, was able to definitively prove that Tamu Massif is one single volcano. Now Sager is returning, with the goal of collecting magnetic data in order to understand how this massive volcano formed.

How Did the World’s Largest Single Volcano Form?

“There are two main hypotheses about how Tamu Massif formed: the plume head hypothesis and the fertile mantle hypothesis,” Sager said. “If we look at the two different hypotheses, they give us different expectations about what the magnetic data will show.”

“There are two main hypotheses about how Tamu Massif formed: the plume head hypothesis and the fertile mantle hypothesis,” Sager said. “If we look at the two different hypotheses, they give us different expectations about what the magnetic data will show.”

If Tamu Massif formed at the ridges, as suggested by the fertile mantle hypothesis, then magnetic ‘stripes’ of thick oceanic crust would have formed at the ridge over time. But if Tamu Massif formed from a massive pulse of volcanism, as suggested by the plume head hypothesis, then lava would have traveled long distances, with no coherent ‘stripe’ formation.

The current data from Tamu Massif tells a conflicting story: there are magnetic ‘stripes’ observed on the north side but none on the south side. However, this data is still far from complete.

Existing Magnetic Data Tells Conflicting (and Incomplete) Story

“The current magnetic map of Tamu Massif looks like someone threw a pot of spaghetti on it. Most of the magnetic data was gathered in the ’60s and ’70s, before GPS navigation, and the cruise tracks are irregular in spacing and coverage,” Sager said.

Collecting a grid of magnetic data using GPS navigation will allow Sager and students to fit in the pre-existing data with the new data, filling in gaps of knowledge and formulating conclusions about Tamu Massif’s formation.

“When the students see data that they’ve collected at sea, they’ll have a very visceral memory of what that really means,” Sager said, pointing out that fieldwork is often an integral part of a geophysicist’s career.

The research cruise will be aboard the R/V Falkor, which is owned and operated by the Schmidt Ocean Institute, a nonprofit organization dedicated to advancing ocean research, discovery and knowledge.

Rachel Fairbank, College of Natural Sciences and Mathematics